Freedom Summer

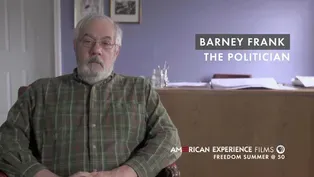

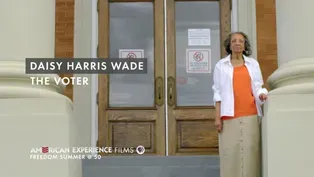

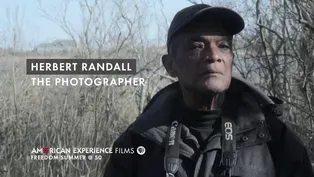

Season 26 Episode 6 | 1h 51m 48sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Shattering the foundations of white supremacy over 10 memorable weeks in 1964.

The story of 10 memorable weeks in 1964 known as Freedom Summer, when more than 700 student volunteers from around the country joined organizers and local African Americans in a historic effort to shatter the foundations of white supremacy in Mississippi - then one of the nation’s most viciously racist, segregated states.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

For Season 26 of American Experience, exclusive corporate funding is provided by Liberty Mutual Insurance, major funding by The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting...

Freedom Summer

Season 26 Episode 6 | 1h 51m 48sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

The story of 10 memorable weeks in 1964 known as Freedom Summer, when more than 700 student volunteers from around the country joined organizers and local African Americans in a historic effort to shatter the foundations of white supremacy in Mississippi - then one of the nation’s most viciously racist, segregated states.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch American Experience

American Experience is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

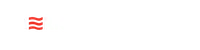

When is a photo an act of resistance?

For families that just decades earlier were torn apart by chattel slavery, being photographed together was proof of their resilience.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipPart of These Collections

Civil Rights

The history of America’s ongoing struggle with race, democracy and justice.

View Collection

The African American Experience

Celebrating the contributions of Black Americans to the American story.

View CollectionProviding Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipWOMAN: ♪ Hear that freedom train a-comin' ♪ ♪ Hear that freedom train a-comin' ♪ ♪ Well, hear that freedom train a-comin'... ♪ KARIN KUNSTLER: Spending a summer in Mississippi taught me a lot about this country.

My high school social studies teacher taught me that we all have rights.

Mississippi Summer taught me that we didn't all have rights.

WOMAN: ♪ They'll be comin' by the thousands ♪ ♪ They'll be comin' by the thousands... ♪ JULIAN BOND: When we began to go to Mississippi, the Black people we met there were not interested in lunch counters.

They weren't interested in sitting in the front of the bus.

There were no lunch counters.

There were no buses.

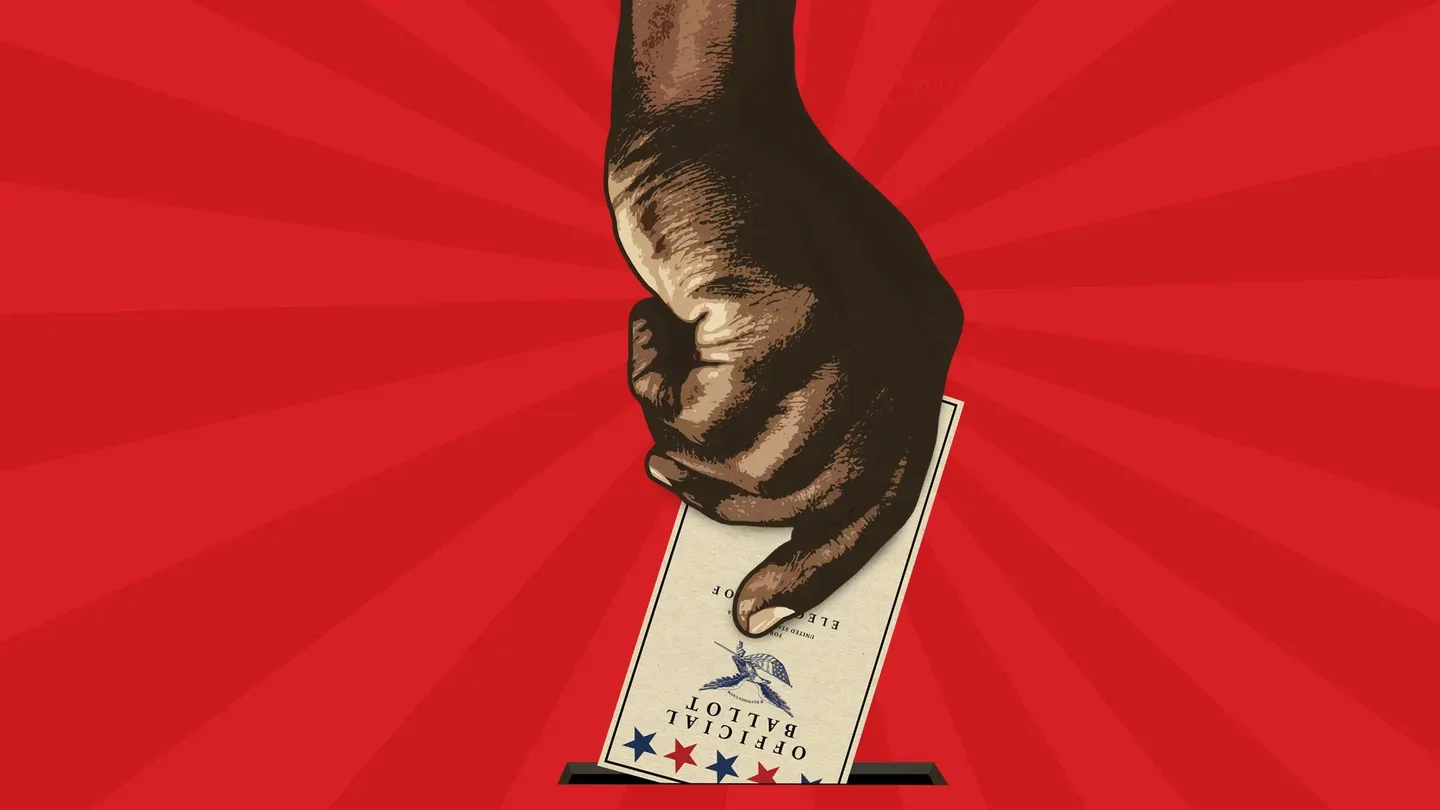

They wanted to vote.

WOMAN: ♪ It'll be carryin' registered voters ♪ ♪ It'll be carryin' registered voters... ♪ PEGGY JEAN CONNOR: I just made up my mind that I was going to be a registered voter.

I never wanted to be a politician.

I just wanted the right to vote.

WOMAN: ♪ Get on aboard... ♪ EUGENE "BULL" CONNOR: I don't want the niggra as I have known him and contacted him during my lifetime to control the making of the law that controls me, to control the government under which I live.

WOMAN: ♪ It'll be rollin' through Mississippi... ♪ CHARLIE COBB: I don't think people understand how violent Mississippi was.

Terrorism led Black people to the obvious conclusion: if they try and vote, they're messing with white folks' business and they can get hurt or killed.

BOB MOSES: We hope to send into Mississippi this summer upwards of 1,000 students from all around the country who will engage in what we're calling freedom schools, community center programs, voter registration activity, and, in general, a program designed to open up Mississippi to the country.

REPORTER: The burned-out station wagon in which the three civil rights workers were last seen has been processed by FBI laboratory investigators... DOROTHY ZELLNER: I knew it was going to be bad.

I didn't dream for a minute that people would be killed.

But it was always in the back of everybody's mind that something... that things, bad things, were going to happen.

So it was terrifying.

But if you cared about this country and you cared about democracy, then you had to go down.

("Going Down To Mississippi" by Phil Ochs playing) ♪ I'm goin' down to Mississippi ♪ ♪ Oh, I'm goin' down a southern road ♪ ♪ And if you never see me again ♪ ♪ Remember that I had to go ♪ ♪ Remember that I had to go... ♪ REPORTER: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a militant group in the South with support from other major civil rights organizations, is readying a massive program called the Mississippi Summer Project, a campaign that may have no parallel since the days of Reconstruction.

♪ ♪ GWENDOLYN ZOHARAH SIMMONS: I'd heard about Mississippi all of my life growing up.

But nonetheless, the fact that the people in Mississippi couldn't vote was just a shock, even to me there in Memphis.

I thought that it was very important to go to Mississippi and make a statement about the horrors that confronted Black people there.

REPORTER: This Ivy League campus is one of the staging bases for an invasion of Mississippi by college students.

The students are being recruited all over the United States, from Harvard to Hawaii.

They will go to live in Mississippi this summer to fight for the Negroes' civil rights.

PATTI MILLER: I first heard about Freedom Summer in the spring of 1964.

I saw a brochure on the bulletin board at Drake University, where I was a student, which is in Iowa.

And it just caught my eye immediately.

♪ ♪ TRACY SUGARMAN: I had been making drawings for corporations and colleges, and my wife, June, felt very deeply about the injustice in the country, as did I.

So we decided that I would take my skills as an illustrator and go to Mississippi.

I was 20 years older than they were, but I was part of the group.

ZELLNER: My job was recruiting.

Students heard about the project either through me or the campus newspaper.

Then they contacted us for an interview and for an application.

ANDREW GOODMAN (dramatized): I am a junior at Queens College majoring in anthropology.

My schooling so far has been oriented toward history and I have a good knowledge of current affairs.

Finally, I have a good deal of experience with racial and religious prejudices in the North and South.

Andrew Goodman.

LINDA WETMORE (dramatized): I have just returned from a spring project on a voter registration drive in Raleigh, North Carolina, where I was filled with an overwhelming desire to clean the rot out of America.

All I can say is that it's very important to me that I play my role in civil rights for the U.S. and most of all for myself.

Linda Wetmore.

ZELLNER: We were looking for people who believed that this was important, who would be respectful to the Black community, who were not nutcases, who were not divas, and who were not people who were going down to show the world how great they were.

This was a majority Black organization with Black people telling white people what to do.

Now, Phil, let's say you're in Mississippi and Bob Moses, who's the director of the project, comes over to you and says, "Phil, will you spend the next four weeks typing index cards?"

Or some other task that you might not care for very much.

What would you react, how would you react to that?

Well, I would certainly say yes, but I would hope that...

I do hope that I can participate more actively in the movement.

If this is where he wants me to be, of course, that's what I'll do.

ZELLNER: We turned down people.

There were many more people who wanted to go.

But from the point of view of safety for the whole project, we had to have people who were as together as you can be when you're 19 or 20.

When we sure that Freedom Summer would actually happen, Jim Forman, the executive director of SNCC, sent a number of people who would be paid field staff into Mississippi to help pave the way.

RITA SCHWERNER: Part of the application process to be considered as part of the field staff was to write a letter of application.

And this is part of the letter that I wrote.

"I wish to become an active participant "rather than a passive onlooker.

"As my husband and I are in close agreement "as to our philosophy and involvement "in the civil rights struggle, "I wish to work near him "in whatever capacity I may be most useful.

"My hope is to someday pass on to the children we may have "a world containing more respect "for the dignity and worth of all men than that world which was willed to us."

REPORTER: For these students, it will be a longer, hotter summer than for almost anyone else in this country.

But they believe their project will be the breakthrough in the civil rights battle.

Their motto: "Crack Mississippi and you crack the whole South."

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ HOLLIS WATKINS: From an early age on, I was told as a young Black boy, "If you see white people walking down the sidewalk, "especially if it's a man, "you step off to the side "and drop your head until he passed by, "because if you didn't, "he might consider that to be disrespectful "and he might hit you, he might kick you, he might beat you."

♪ ♪ ANTHONY HARRIS: My grandfather, he would take me with him, downtown Hattiesburg, to, to pay bills.

And I remember my grandfather wore a straw hat with this colorful blue band around the, the hat.

And as a white person approached us on the sidewalk or crosswalk, he would tip his hat in what I would call an extra show of deference.

And by the time my grandfather and I reached back to his house, we had bowed so many times to, to white people.

They taught young kids like myself how to play the role of that second-class citizen.

WALLY BUTTERWORTH: There are a lot of phonies who will stand up and tell you that, "Oh, well, all are equal in the eyes of God."

How silly can you get?

Christ himself was the greatest teacher of segregation.

BRUCE WATSON: Mississippi really stood like an island of resistance.

There were only 6.7% of Blacks who were registered to vote prior to Freedom Summer, compared to 50%, 60% or 70% in other Southern states.

Most of the rest of America didn't seem to care, and that's what Freedom Summer was about.

"If we bring white students and Black students "from all over the country, "then everyone will pay attention to Mississippi.

"We'll bring America to Mississippi, because America is not paying attention to Mississippi."

WILLIAM WINTER: In the '50s and '60s, particularly in the old plantation agricultural areas of the state, African Americans made up at least half, and in some cases 70% or 80% of the population.

And, in some counties, of course, there was a realistic understanding that if Black people voted, they probably would be electing Black officials.

A lot of white people thought that African Americans in the South would literally take over, and white people would have to move, they would have to get out of the state.

WILLIAM SIMMONS: I was born in Mississippi and I am the product of the society in which I was raised, and I have a vested interest in that society, and I, along with a million other white Mississippians, will do everything in our power to protect that vested interest.

WILLIAM SCARBOROUGH: There was no Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi during this early period.

There wasn't any need for one.

The Citizens' Council was doing everything that the Ku Klux Klan would have done.

There were a lot of prominent people who were members-- businessmen, bankers, lawyers, politicians.

I joined it because I believed in what they were doing and I believed in trying to preserve the society in which we lived.

(fanfare playing) ANNOUNCER: This is the Citizens' Councils Forum, the American viewpoint with a Southern accent.

CHORUS: ♪ I wish I was in the land of cotton ♪ ♪ Old times there are not forgotten ♪ ♪ Look away!

♪ JOHN DITTMER: The Citizens' Council was really running the state of Mississippi.

It was part of the whole apparatus of, of a white supremacist society that you had the local police, you had the registrar, you had everyone involved in the Citizens' Council.

They succeeded in preventing almost all Blacks who attempted to register from registering to vote.

COBB: Political participation was something reserved for whites.

And if Blacks sought it, they could get hurt in lots of different ways, ranging from economic reprisals, loss of jobs, or if you had a business, restrictions are being placed on your business, or if you had a loan, your loan being called in.

BOND: The common theory about Mississippi was that you could not attack Mississippi from the inside.

It had to be attacked from the outside.

You had to stand away and say, "This is an awful place and it ought to fix itself."

♪ ♪ But Bob Moses and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee said, "No, that's not true; we can do it ourselves."

WATSON: Bob Moses was a high school teacher in New York City.

He went South in 1960, originally just feeling he had to go, had to get involved.

SNCC sent him to Mississippi.

He started going around on his own in the rural areas where people simply didn't go and challenge the status quo.

ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON: What made him stand out was not only his sheer courage, but his calm courage.

I can't tell you that Bob Moses was afraid, 'cause he never showed it.

(chuckling) He just went about his work and there was this, this calm sense of mission.

IVANHOE DONALDSON: Bob went over there by himself in 1961, and by the end of '61, maybe there were five or six SNCC people in the state.

In '62, maybe there were 18, 19.

And in '63, maybe there were 23, 24.

And we'd have a staff meeting, we all could fit in one little room.

MOSES: Young people working with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee-- or SNCC, as we call it-- are characterized by a restless energy.

They seek radical change in race relations in the United States.

The world is upset, and they feel that if they are ever going to get it straight, they must upset it more.

♪ ♪ NORTON: I don't want anybody to think that we were a bunch of really brave Negroes running around Mississippi.

That's not what we were.

The reason that SNCC, as it were, opened up the Delta is, we were young and foolish.

We didn't have the, the very complete understanding of what that risk was.

♪ ♪ But what impressed me was that there were Black Mississippians who did know.

Who did know how dangerous it was.

BOND: Well, we met this cadre of older people who had been fighting.

They were eager for our help and, and glad we were there.

♪ ♪ MOSES: They knew that the key to unlocking Mississippi revolved around the vote.

And the access for Black people to power at that time has got to be through the vote.

♪ ♪ What was useful was that I was open and accustomed to listening.

COBB: What we were trying to do was to organize these communities to take possession of their own lives.

For the last hundred years, the ability of Black people to control their own destiny had been taken away from them.

(woman talking in background) IDEL CREST: Hi.

Hey, how are you?

All right.

I'm Idel Crest, and I'm working for the board of registration... WATKINS: When I got hooked up with Bob Moses, it was very simple: go out through the community, you knock on doors, talk to people.

The only way to, to better your life and better the lives of your children is to go down and register to vote.

If you're not a registered voter, you're not a first-class citizen, ma'am.

CHARLES McLAURIN: We would tell them that if they registered and voted, they could elect the sheriff, and that the, the intimidation on the part of the sheriff's office and his deputies, they could change that.

One of the things that I always tell them is that we could stop Mr. Charlie from lynching us.

COBB: You're sitting on front porches or you're walking out into a cotton field, or maybe you're at the juke joint having a beer.

What we were doing was embedding ourselves in these communities.

You have your certificate showing that you are a registered voter?

They haven't give it to me yet.

Well, you aren't a registered voter, mister.

We want you to come down to the courthouse tomorrow.

COBB: Immediately what you found out you were dealing with was fear.

CREST: So why not go tomorrow?

We will furnish your transportation, so that's no excuse.

COBB: They would say, "You're right, boy.

"We should be registered to vote.

But I ain't going down there to mess with them white people."

Would you like to go to both of these polling places?

No.

COBB: We did not get a large number of people to try and register to vote.

And then within that small group of people who did try and register to vote, very few of them actually got registered to vote.

Other people are standing in the courthouse.

We can't see why we have to stand out here in the rain in order to register to vote.

It's a denial of our constitutional right.

Your section of the constitution that I choose for you is number 48.

DITTMER: The registrar had total control over who was accepted and who wasn't.

The voting form was one of the most complicated you would ever, ever have.

And as part of that, each person would have to interpret a section of the state constitution.

PEGGY JEAN CONNOR: We had people who taught in colleges.

We had people with Ph.D., master degrees, and all, and they couldn't pass.

You had to be white.

CLERK: No, Jennings, you didn't pass it.

You see there?

You didn't fill out the... Look, there, you just filled out that part and look, you didn't write anything in there.

You didn't pass it.

ED KING: Sometimes, the sheriff would walk into the room while they were taking the voting test and say, "Annie Mae, don't you work for my mother-in-law?

"My mother-in-law would be horrified "if she knew you were taking this test.

"Now, Annie Mae, I'll tell you, "if you'll just put that paper down, I'll tear it up and I won't tell my mother-in-law."

♪ ♪ DITTMER: In some counties, when people went in to register, why, their names would appear in the newspaper the next day.

That could have recriminations for all members of their family.

It could mean they would lose their job.

There were real consequences to, to taking this risk.

It wasn't simply that you would go down and get turned away.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ McLAURIN: On August 31, 1962, we had 18 people to register.

Everybody went into the registrar's office, took the literacy test, came out, and as we were leaving the city, the bus was stopped by the police and the driver was arrested.

Everybody on the bus was afraid.

And then after a while, there was a, a little smooth, uh, song.

Uh, you know.

♪ Paul and Silas bound in jail ♪ ♪ Had no money for to go their bail ♪ And somebody said, "That's Fannie Lou Hamer."

FANNIE LOU HAMER: I went down the 31st of August to try to register.

And after I had gotten back home, Mr. Marlo told me that I would have to go down and withdraw my registration or leave, because they wasn't ready for that in Mississippi.

And I said, "Mr. Marlo, I'm trying to register for myself."

So I had to leave that same night.

MOSES: She has this confrontation, then leaves the plantation and comes into Ruleville and eventually becomes someone who is a SNCC field secretary.

One of the, the important things about recruiting Fannie Lou Hamer was her ability to move people.

Fannie Lou Hamer brought a new kind of spirit into the movement.

And she, I think she...

It kind of rejuvenated all of us.

HAMER: I've been tired a long time in the state of Mississippi.

Living in the county with James O. Eastland, the senator, Senator Stennis, to go to Washington and tell the people that the people of Mississippi, the Negroes, are getting along good and we're satisfied.

But I want him to know this, both of them: we're not satisfied and we haven't been satisfied a long time.

HARRIS: We'd been accustomed to men standing up and challenging the movement, but here is a woman, a Black woman.

And her message to us was, "Don't give up.

"Freedom is not free.

"Keep fighting, keep fighting, keep fighting."

♪ ♪ DONALDSON: As SNCC became more active in the Delta-- the Mississippi Delta, where Greenwood is, in the heart of Leflore County-- we started to create visibility around voter registration and people started going to the courthouse.

If people tried to vote, they would push them off the land so they had no place to live.

They took away their homes.

African American people there who had small businesses, the banks called their notes.

COBB: Even though there were very few people being brought down to try and register to vote, the white power engaged in an act of reprisal directed at the entire Black community.

What they did was shut down the commodities program.

What it was was government surplus food that was sent to poor rural areas.

The county officials said, "Well, no, we're not gonna have that."

Which is essentially, put Black people and poor people in a position where they could starve during the winter.

And this was an especially bad winter.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ AMZIE MOORE: I just keep wondering how they're going to eat, and what they're going to wear, because they have no money, they have no food, and they have no clothing.

They have no way to buy food and clothing.

We have appealed to people all over the United States to send food and clothing in.

COBB: What would happen next would eventually reshape the direction of the movement in Mississippi.

Dick Gregory was then a big-time comedian, flies into Greenwood, Mississippi, in his own chartered airplane full of food to meet the need as a result of this cut-off of commodities.

REPORTER: Dick, how much food did you bring with you on this trip?

We brought something like 14,000 pounds on this trip here.

Canned food, milk, baby food, cereal, wheat, flour, sugar, potatoes... DITTMER: You had the news media coming in, and soon these pictures were going out all over the world of what was happening in Greenwood, Mississippi, where, several months before, it had been very much of a small operation with little visibility at all.

REPORTER: City officials deny the winter-long cut-off of food allotments was retaliation for the Negro voting drive.

But the sharecropper who tries to register to vote often faces the threat of losing his job and being put off the plantation.

Bob Clark, ABC, Greenwood, Mississippi.

COBB: It shows us that it's possible to make the country pay attention to Mississippi.

Gregory's action indicates to Mississippians that they didn't have to be alone.

DONALDSON: The American people only see what's on television at night on the evening news.

So where Dick Gregory created a lot of drama and the cameras were there, and then it went away, we wanted to figure out how to do that for the entire summer, to invite the children of America into Mississippi so that they'd pay attention to what was going on in Mississippi.

And from that, the Mississippi Summer Project evolved.

♪ ♪ COBB: Most of the organizers in Mississippi were opposed to the idea of the Mississippi Summer Project, which meant essentially bringing down...

I think the number we were talking about was roughly 1,000 students.

I was one of the people who was opposed to Freedom Summer.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ KING: People in the movement were willing to die, but we didn't want to die in obscurity.

So if we brought in students, their colleges, their parents would focus on Mississippi.

I supported bringing the volunteers in.

COBB: The experience of people like Mrs. Hamer was that people coming from the outside was a good thing.

Mrs. Hamer backed me up into a corner and said, "Well, Charlie, I'm glad you came."

(laughs) "What's the problem with having more people come?

How can you be opposed?"

And eventually, we decided to go ahead with Freedom Summer.

♪ ♪ Once the decision was made to have a summer project, there's a series of meetings and discussions going on then about what the summer project is going to do.

REPORTER: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a militant group in the South... Well, there were three components of Freedom Summer.

One was voter registration, which would be going door-to-door, knocking on doors and asking people if they were willing to go down to the courthouse to register to vote.

A second and very important component of Freedom Summer were the freedom schools.

They would teach things that they were not taught in Black schools in Mississippi.

Black schools in Mississippi couldn't teach about Black history.

They couldn't teach about Black literature.

So freedom schools were set up to do exactly that.

And finally there was the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

It was a parallel political party which basically said that, "We will send our own delegates "to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City "at the end of August, "and we will challenge "the all-white delegation to see who would represent the state of Mississippi at the convention."

White Mississippians believed that what was going to happen in the summer of '64 was something that not only they had to be psychologically prepared for, they had to be militarily prepared for it, as well.

It shows you the hysteria that was evident in much of white Mississippi.

REPORTER: In Jackson, Mississippi, a city of 100,000 whites, 50,000 Negroes, the mayor has prepared for this summer's activity by increasing the police forces, by passing new ordinances against demonstrations, and by purchasing a steel-plated vehicle, a riot control car known locally as Thompson's Tank, named for Mayor Allen Thompson.

We are prepared to take care of any law violations to keep down violence.

REPORTER: In addition to Thompson's Tank, armor-plated and equipped with nine machine gun positions, the arsenal includes cage trucks for transporting masses of arrested violators, search light trucks, each of which can light three city blocks in case of night riots... (firing) The Citizens' Council had convinced people that the Klan wasn't necessary, that it was bad publicity, and that they could keep schools from being desegregated, they could keep lunch counters from being integrated.

But by 1964, when they see the volunteers for Freedom Summer, it was clear that they couldn't, and that's when the Klan starts to ride.

(flames crackling) WATSON: The Klan rose up as one in Mississippi.

One night in April of 1964, crosses were burned all over Mississippi.

They claimed that they had 90,000 members, and they were going to resist what the Klan called the "Nigger-Communist Invasion of Mississippi."

So Mississippi, on the eve of Freedom Summer, was on a hair trigger.

♪ ♪ SCHWERNER: There was very much a recognition and a debate about, is it responsible to bring all those kids into the state, most of whom are probably far too naive to understand what they were getting into in terms of the violent nature of the place?

Are you, are you doing this to use people as, as fodder?

♪ ♪ The thought was, "Well, you know, "we'll do this orientation at Oxford, Ohio, "and we'll try and tell these kids what they're getting into and make it clear that they really don't have to go."

But you know, I don't know that that really could begin to prepare people.

GWENDOLYN ZOHARAH SIMMONS: My grandmother said, "We've heard that you're planning on doing something "really crazy-- "going to Mississippi with those SNCC folk-- and I'm never gonna permit it."

LINDA WETMORE HALPERN: We went to Oxford.

A group of us from Massachusetts met in Boston.

We drove across, sharing driving, you know, for different hours.

We drove straight through, people sleeping.

I know I drove very fast.

Several of us drove up to Oxford in the blue station wagon that we used in Meridian.

GWENDOLYN ZOHARAH SIMMONS: With my grandmother, my mom and dad pleading, threatening, I just said, "I'm leaving."

A girlfriend drove me to the bus station, and my grandmother's parting words were, "If you leave, don't ever come back."

♪ ♪ SUSAN BROWNMILLER: And I remember one young woman saying, "We're gonna settle this problem, "and then it's on to the Indians, and we're gonna settle that, too."

I mean, there was that kind of unbelievable idealism.

GWENDOLYN ZOHARAH SIMMONS: I can remember people saying, "Well, how bad can it be?"

(laughing): You know, because they had no idea.

And even I didn't think that they might be beaten or killed.

And, in fact, that was one of the ways that I sort of calmed my fears.

I thought that their presence would be a mediating factor.

♪ ♪ MOSES: The SNCC field secretaries arrive in Ohio and it's, in some senses, it's oil and water.

So erupts, you know, one-on-one in different kinds of interactions between the students and the field secretaries.

COBB: The need for the volunteers and the presence for the volunteers represented our inability, after three years, to make significant inroads into changing Mississippi.

So we had to reach out to this larger group, which was predominantly white.

And many of us were still not entirely comfortable with it.

CHRIS WILLIAMS: The tension between the volunteers and the SNCC staff, who was almost entirely Black, became evident right away.

They were, like, "We're going to take these greenhorns back to Mississippi "and be the tip of the spear of the Civil Rights Movement, "and these people are like to get us killed, because they don't know what they're about to do."

And they're saying, "These people look like they're just about beyond hope."

SNCC WORKER: The police are going to harass you.

They're going to pick you up on the road, they're gonna trump, gonna put trumped-up charges on you, you're gonna wind up in jail.

I suggest we be a little more serious about this thing.

GWENDOLYN ZOHARAH SIMMONS: One of the things that was done at the orientation was to instruct the white students, particularly, that you're going into a situation where you will have to follow the directions of Black people.

You will be living in Black homes.

You will have to live according to the way they live.

You will, your life will depend upon you following directions.

And, of course, these white students had never been in a situation like this.

("Simple Gifts" playing) BOND: In order to orientate the Freedom Summer workers, we showed them this movie.

It featured Theron Lynd, who was the registrar in Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

REPORTER: Theron C. Lynd, circuit clerk and voting registrar of Forrest County, Mississippi, is one of the most powerful men in America.

He and the 81 other county registrars in Mississippi have the power under state law to decide who can and who cannot vote.

Theron Lynd is your, is your stereotypical racist bad guy-- a big, burly, cigar-chomping, tobacco-chewing, aggressively racist white man.

LYND: That's right, that's a section of the constitution of the State of Mississippi.

All right, then, when you get over here and answer the question 19... COBB: And the summer volunteers see him and start to laugh.

People coming up from Mississippi were tired, exhausted, suspicious of the summer project.

So the reaction to that laughter was hostile.

"You're not taking Mississippi seriously.

"You, you think this is something funny, "something to be laughed at-- no.

What you're looking at has cost people their lives."

SUGARMAN: And when the lights came up, the young SNCC leaders said, "We have to know you, we have to love you, but we don't understand you."

They really were furious, and went on at great length to say, "You're coming out of a different place.

I don't know if you should be going with us."

These white kids were unsteady vessels.

They, they weren't at all sure that, that these were the allies they wanted.

♪ ♪ WATSON: They stayed in the auditorium for a few hours talking and arguing, and they really went at it, but I think it really broke the tension.

It brought out these underlying resentments.

It brought out the differences between the two and it highlighted them.

And, above all, it brought out the fact that they were all in this together.

♪ ♪ And from then on, a lot of the tension was broken and they realized that they were really one in this, and that they were going to go down and, and do this together.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ SCHWERNER: At the end of the first week, we got a call in Oxford.

People at the Mount Zion Church had been beaten up badly and the church was burned.

My husband, Mickey, and James Chaney decided that they needed to go right away to see how people were and to provide whatever support they could.

♪ ♪ Andy Goodman was going to be one of the volunteers working out of the Meridian office, so they decided that all three of them would go.

We were in the dorm room that we had been assigned and Mickey kissed me goodbye and said, "I'll see you at the end of the week," and left.

And they drove down in the blue station wagon.

♪ ♪ GOODMAN (dramatized): "Dear Mom and Dad, "I have arrived safely in Meridian, Mississippi.

"This is a wonderful town and the weather is fine.

"I wish you were here.

"The people in the city are wonderful, "and our reception was very good.

All my love, Andy."

It was close to around 6:00 or 7:00, around 6:00, 7:00 in the evening.

And a call came in from the Meridian people wanting...

They had not heard from Mickey and James Chaney.

I just knew that something had to be wrong.

SCHWERNER: It was early Monday morning, around 1:00 or 2:00 in the morning, when someone came to the dorm room that I was using and woke me to say that the men had not returned, and that was how I first heard of it.

♪ ♪ GWENDOLYN ZOHARAH SIMMONS: Everybody was to come into the auditorium for this session.

They had this extremely solemn look on their faces.

And then they told us that three workers who had been at the orientation and had left early, they had disappeared.

SCHWERNER: I urged people to contact their families and have their families contact their congressional people to indicate that we believed that there certainly was a possibility, given the fact that so many hours had gone by and... that they couldn't be located, that they might have been killed.

REPORTER (on TV): The three civil rights workers who disappeared in Mississippi last Sunday night still have not been heard from.

A search has thus far produced only one clue, the burned-out station wagon in which the three were last seen riding.

Andrew Goodman, a 20-year-old college student from New York... GWENDOLYN ZOHARAH SIMMONS: Learning that three of our members, two of whom were white, had disappeared really blew away all my ideas that possibly we would have protection from the fact that the majority of the summer volunteers were white.

I knew now that that was not the case, that everybody was in grave danger, and that these Mississippians would kill all of us, white and Black.

♪ ♪ HALPERN: Bob said that, "There is no guarantee "that you will get out of this summer alive, "so just know that.

It's up to you if you want to continue on."

So he left us all to the phones, and we all went.

We were told to call home.

REPORTER: Did you talk this over with your parents before you made the decision?

Yes, I discussed it with them, and...

They felt, of course, what I feel, and that is fear of, of what might happen there.

My mother and father did not ask me to come home.

They asked me to do what I thought was right.

So I boarded the buses.

WOMAN: ♪ I'm goin' down to Mississippi ♪ ♪ I'm goin' down a Southern road ♪ ♪ And if you never see me again ♪ ♪ Remember that I had to go ♪ ♪ Remember that I had to go ♪ ♪ It's a long road down the Mississippi ♪ ♪ It's a short road back the other way ♪ ♪ If the cops pull you over... ♪ WILLIAMS: We came down the interstate from Memphis into Mississippi.

It must have been about 4:00 in the morning.

There was a billboard right at the state line that said, "Welcome to Mississippi, the Magnolia State."

And of course there was a little bit of dread in seeing that, but what was more significant was that there were two Mississippi highway patrol cars parked under the sign, and as the buses came by they pulled out and followed us.

So at some level they knew exactly when we were coming.

WOMAN: ♪ For an out-of-state car ♪ ♪ And he thinks he's fightin' for his land... ♪ MOSES: What really is important is that they get down and kind of just melt away into the Black population.

♪ ♪ If we could just get everybody through the entry point and into the community, the Black community will house them and also harbor them.

BOND: The genius of the Freedom Summer is that these volunteers were spread all over the state.

The Freedom Summer workers are everywhere.

They are in almost every little big town.

Almost every place where you can go, they are there.

REPORTER: Yesterday the first 200 civil rights workers arrived in Mississippi and fanned out over the state.

Another 800 will follow.

The students were assigned living quarters in Negro homes from a central office.

When Charles and Doug came by the house and told us that they need some homes for the civil rights workers to live, I said, "Well, I don't have much room, but yeah, we'll be happy to do it, you know," and then I told my husband about it.

He said, "Yeah, they can stay here."

I felt the time had come to help make a change.

I had three sons and I didn't want them to go through what I had gone through and what I had seen.

So I was determined to help make a change.

Say, "Well, they'll have to take the twin beds and the boys have to double up."

They were happy to know that somebody was coming from... All we have to do is say, "from the North."

(laughs) HARRIS: We were now going to have a white person living in our house.

So it was a special time, it was an exciting time.

We weren't sure what they were going to be like because even though we had seen white people on television and in person, but to actually have someone living in our home, to spend time with us, to share meals together, that was a much different type of relationship than what we had been accustomed to.

ROSCOE JONES: They became a part of the Black community.

I don't know of any place that they could run into a white neighborhood and be accepted because they were outsiders.

They became the closest thing to being a part of the Black community as anybody can be because they had no choice.

REPORTER: Walt Kaufman, you're from California.

What's it like to come into a situation such as exists here in Neshoba County, and as a white man come to work for the project?

Well, what I'm most impressed with is the response of the people here who have been intimidated and terrorized for years and who know that our presence here probably poses some danger for them and yet they've shown tremendous courage and amazing hospitality to us.

They've helped to feed us, they've encouraged us, they've warmed us with their... just friendship and smiles.

And it's an extremely impressive experience to me.

SUGARMAN: Everybody knew that we were going home at the end of the summer.

The people that took us in were going to stay.

So they were there for the reprisals, for the anger that the white community had all the power to bring to bear on them.

And they did it because they really believed that we were there to help, and they'd never seen white people who had come to help in their whole lives.

♪ ♪ SIMMONS: One of the most wonderful things about 1964 Mississippi Summer were the freedom schools.

COBB: The state of Mississippi deliberately and systematically kept Black people uneducated and ignorant, and then turned around and made education a requirement in order to participate in the political process.

We were able to do the freedom schools in the summer of 1964 because we had almost 1,000 students coming to the state of Mississippi, thus the human resources to actually, you know, conduct classes.

MALE VOLUNTEER: We hope to find and develop and mold local leadership among the young people.

We also hope to promote a better self-image among the local Negroes.

♪ ♪ JONES: We would send out mass flyers and everything to the churches, telling people about the freedom school, what the freedom school was going to entail, the courses, the activities.

We got the preachers involved, we got the kids involved.

♪ ♪ McLAURIN: Black people couldn't go to the library.

It was for whites only, and so here they are, got their own library now.

They would come excited to be exposed to the teaching and to browse the books.

HARRIS: In the public schools where I was in school, I had never heard of Dr. Seuss.

It was at freedom school where we actually not only read the story of "The Cat in the Hat," but we acted it out.

Having our lives enriched by these activities really made a huge difference in my life.

SIMMONS: We taught African-American history, civics, African culture, African dance.

They were learning Black history that they were reading books that had been written by Blacks that they'd never heard of.

How were slaves first introduced in America?

MALE VOLUNTEER: As we saw back on this world map over here, America started picking up slaves along here and then bringing them back.

CHRIS HEXTER: What we were trying to do that summer is get people to talk about their own lives, talk about good and bad, and talk about ways in which you could bring about change.

I think that was very much the drive of the program.

FEMALE VOLUNTEER: They had a sense of being needed by something much bigger than themselves and a sense of being able to handle the problems that they were needed for.

They did it by asking questions and by being encouraged to feel free to ask questions.

HEXTER: They were rarin' to go.

We were just kind of like the catalyst.

We were agents of information and agents of a different world, so I mean just the very fact that we were talking about a world that they didn't know, or didn't have much experience with was exciting to them and also to us.

♪ ♪ McLAURIN: We set them up for the little children to come, and every day we'd have classrooms of adults, people 50, 60 and 70 years of age.

The adults came to the freedom school to learn just like the little children.

HARRIS: Being in freedom school planted a seed in my mind that things are going to change, things are going to be different.

And Freedom Summer helped to give us that courage, it helped to give us that hope, it helped to give us the reason to believe that it was going to be different.

(engine droning) REPORTER: This is backwoods Mississippi and its 2.5 million acres of swamp.

Damp and clammy country, as hostile as the attitude of its white people to civil rights.

The green slime that sprawls for miles may hide forever what's happened to Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner.

As the search for the men intensifies in the swamps, there are those in Mississippi who do not seem disposed to see this as a personal tragedy.

One of them is Mississippi's former governor, Ross Barnett.

We will treat anyone with great respect here in Mississippi, anyone who comes here, as long as they do not disobey our laws, but we will treat the people who come here, these children, like any other backward children.

MAN: ♪ Go, Mississippi ♪ ♪ Keep rolling along ♪ ♪ Go, Mississippi ♪ ♪ You cannot be wrong... ♪ WILLIAM SCARBOROUGH: They're outsiders coming down here trying to change the world and there's natural resentment.

I mean, that's common sense.

MAN: ♪ M-I-S-S-I-S... ♪ ♪ S-I-P... ♪ SCARBOROUGH: We didn't think those people understood what kind of society we had here.

You know, these college students would sit up there at Oberlin and there'd be a articulate, well-groomed Black person sitting next to them, and they assumed all Blacks were like that and they weren't.

MAN: ♪ Go, Mississippi... ♪ They're coming for the purpose of registering Blacks to vote.

And since this state had the highest percentage of Blacks of any state in the United States, that poses a real threat politically.

There was a siege mentality, us against them, and I hated them.

MAN: ♪ ...singing your song ♪ ♪ M-I-S-S-I-S... ♪ ♪ S-I-P-P-I ♪ (song ends) WILLIAM WINTER: Let me state as clearly as I can what the mindset of the state of Mississippi was, encouraged and emboldened by the utterances of its politicians.

If the white people of Mississippi will just stay together, will just stick together, there is no force in this country that will cause segregation to be ended.

That was the mindset.

BARNETT: We face absolute extinction of all we hold dear, unless we are victorious!

We can win, my friends, if we are organized in every community in Mississippi and all over this nation of ours!

We must be stronger than the enemy!

We must be strong enough to crush the enemy!

(applause) MOSES: They're caught in a circle which, if there are people who want to break out, they don't know how.

They don't have a chance.

They just... white people are probably more oppressed or... in terms of their ability to speak than Negroes.

BARBARA JAN NAVE: In the South, you were expected to live a certain way.

♪ ♪ You just didn't step outside the bubble.

In August of 1963, I was crowned Miss Mississippi and would spend the next year representing Mississippi all over.

♪ ♪ WATSON: Red Heffner and his wife were loyal Mississippians.

Their daughter was Miss Mississippi, and they really believed that if they just invited a couple of white volunteers over to their house in McComb, just for dinner, just to find out what was going on, nothing, nothing would happen, nobody would object, but they miscalculated badly.

NAVE: The whole purpose was just to keep the peace, to try not to have any more bombings, try not to have any more killings.

They came over just to have tea or whatever, or coffee.

MRS. HEFFNER: Then shortly after that, a man called, a neighbor, that we didn't know very well, and he lives a good distance from us, and said that the neighbors were upset about this car that was in front of our house and who did it belong to.

About ten minutes later, Red Heffner opened his front door and there were all these headlights glaring at him, like something out of a bad movie, and people started shouting things, and they just barely got the people out of there, and from then on, the Heffners' life in Mississippi was pure hell.

I went downtown one day, and friends that I had known for ten years would turn and walk away from me, or hang their heads.

Some would speak and walk on as if I had leprosy or something.

NAVE: My father was asked to move out of his office.

So he lost his business.

Our, you know, our little dog was killed.

I came home to visit because I was still traveling as Miss Mississippi and the FBI wouldn't let me go home.

I had to stay in the Holiday Inn because they had heard that the house was going to be bombed.

It's just gotten too low.

To the point that we couldn't take it any longer.

WINTER: It's a mark of the obsession that so many white people had in this state at that time with maintaining segregation that made them turn on their neighbors, on their friends.

The Heffners were ostracized socially and finally had to leave the state.

NAVE: They left everything they'd ever had behind.

When all your roots are in one place, it breaks your heart.

♪ ♪ WETMORE: I saw in Mississippi a white population that I had never even imagined existed.

The vile, the absolute hatred that was in their eyes when they saw us coming, was... it-it scared me.

FEMALE READER: "It's night, it's hot.

"Violence hangs overhead like dead air.

It hangs there, and maybe it will fall, and maybe it won't."

FEMALE READER: "Although I was extremely tired, "every shadow, every noise, the bark of a dog, "the sound of a car, in my fear and exhaustion I turned into a terrorist approach, and I believe..." MALE READER: "I wake up in the morning sighing with relief "that I was not bombed "because I know that they know where I live, and I think, "'Well, I got through that night, 'and I have to get through this day,' and it goes on and on."

There were always moments when I just wondered if I could make it through that day to the next one, and then to the next one.

Just always questioning, always wondering.

Every time I walked out on the street I, in my mind, I expected a bullet to hit me.

FEMALE VOLUNTEER: They threw a stick of dynamite where, now?

Now, what damage did it do?

DITTMER: Freedom Summer was one of the most violent periods in Mississippi history since the end of Reconstruction.

There were over a thousand arrests made.

REPORTER: The explosive, nobody knows what kind or how much, was apparently placed up against the house or rolled up against the house.

DITTMER: 65 buildings were either bombed or burned, including 35 churches.

There were a hundred or so beatings.

I mean, this was going on all over the state.

SIMMONS: And then there was the whole issue of white women living in Black homes.

I mean, that just infuriated them.

Take these, uh, white women that've been imported in here.

They call 'em white women, I could call 'em a light colored rat.

They stay and sleep in the same damn house that the niggras do.

And then tellin', tellin' me that they, that they're not sexual relations at.

Why, that is, that is, for the... for the birds.

Even walking down the street in an interracial group was kind of a no-no.

I remember being arrested and being asked a lot of questions.

And the sheriff wanted me to describe the size of Black men's penises.

They were obsessed with sex.

I don't think we were obsessed with sex.

But it was a clear message that that's all they thought we were doing.

BOND: If you got in any kind of trouble at all or anybody was threatening to you, there was nobody you could go to and say, "Help me."

You couldn't go to the police, you couldn't go to the sheriff, you couldn't go to the state officials.

All of these people are hostile and probably the people who are threatening you themselves.

So there is nobody you can appeal to.

WETMORE: I was walking along a road.

We were told never to leave the place we were staying by ourselves.

They jumped out of the car.

They started calling me, "Hey, nigger lover!

"We got you, we finally got you.

"We ain't killed ourselves a white girl yet.

You're gonna be the first."

They get this lynch rope.

It really was a noose like you see, like I had seen in the pictures of the hangings, right.

They put this noose over my head.

And it's attached to a long rope.

They jump back into the car, and I just saw myself being dragged to death.

I'm walking like this.

And they're laughing and calling me all kinds of names.

And then they moved along, slowly, a little bit faster.

I'm walking faster.

And it was like, okay, this is it.

And then they dropped the rope.

And I just stood there.

Of course we had to wear skirts.

We weren't allowed to wear pants in those days, so we all had our little shifts on and everything.

I peed all over myself.

Just stood on the... and just peed.

♪ ♪ RUBIN: "The day-to-day work was canvassing.

"The work itself is as simple as it is tedious.

"We walk down these dusty red country roads "in the Negro sections, "go from tumbledown house to tumbledown house, "and if they come out to the porch or let us in, "we talk to the people.

"That's it.

"That's what we do.

That's what the segregationists are trying to stop."

♪ ♪ SUGARMAN: My motivation for drawing was I wanted to make sure that I was capturing the flavor a moment, the intensity of a moment.

And you are in that situation, everything becomes memorable.

The intensity of those situations become indelible.

That happened to me twice in my life.

One was on D-Day, and the other time was in Mississippi.

KUNSTLER: The work was frustrating.

There was a very small return for the number of doors we knocked on.

You could see in people's faces the struggle they were going through.

Many really wanted to register but were fearful.

"I'm not going to register to vote because I work for a white family and I think they might fire me."

Or "I've heard that houses get burned down when people go to register to vote."

Or "I'm worried about my kids."

We were doing something very positive but also in the backs of our minds was the negative that could befall someone we were talking to.

Because the danger was real.

It was absolutely real.

♪ ♪ REPORTER: Late this afternoon, the search for Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner shifted to the Pearl River near Philadelphia, Mississippi.

Boats carrying game wardens and FBI agents are now dragging the river.

REPORTER: Have you seen the spot down here, sir?

MAN: That's right.

REPORTER: What do you think of this?

I believe them jokers planned it and sitting off up there in New York, laughing at us Mississippi folk.

REPORTER: Can you tell me what you think of this whole thing?

WOMAN: Well, I believe it's a big publicity hoax, but if they're dead I feel like they asked for it.

KUNSTLER: It was always on our minds, and we were constantly aware that they had not been found.

There was a pall over the whole project because of that.

REPORTER: In Meridian, the wife of missing Mickey Schwerner, Rita Schwerner, flew from Oxford.

BOND: Rita Schwerner plays an important role here.

This is her husband, after all, who is the leader of the three missing men.

And she puts a face on them and she plays an enormous role in making this seem like these are real people and we need to pay attention to these real people who something terrible has happened to.

RITA SCHWERNER: They're being held somewhere, or something happened, and I am going to find the answer.

If this means driving every back road, every dirt road, every alley in the county of Neshoba, I will do it.

DOROTHY ZELLNER: The press swarmed all over her, and I think they wanted her to cry, and they wanted her to be a new widow, that they would catch her at the moment of her widowhood, and she wouldn't play.

I personally suspect that if Mr. Chaney, who is a native Mississippian Negro, had been alone at the time of the disappearance, that this case, like so many others that have come before, would have gone completely unnoticed.

SCHWERNER: I did have some sense that if the story was allowed to deteriorate into, "Oh, this poor little white girl," that, um... it would, um... it would be offensive to everyone concerned.

WATSON: Rita went on to the White House and she met Lyndon Johnson, and he welcomed her to the White House and she said very bluntly, she said, "Mr. President, this is not a social call.

I've come to find out where my husband is."

And she got chewed out by the press secretary, who said, "You don't talk to the president of the United States like that."

Rita simply said, "We do."

JOHNSON: I saw this Mrs. Schwertner this evening, the wife of the missing boy.

J EDGAR HOOVER: Yeah.

She's a communist, you know.

JOHNSON: No, but she acted worse than that.

HOOVER: Is that so?

JOHNSON: Yeah, she was awfully mean and very ugly.

She came in this afternoon.

She wants thousands of extra people put down there and said I'm the only one that has the authority to do it.

I told her I'd put all that we could efficiently handle and I was going to let you determine how many we could efficiently handle.

REPORTER: On Thursday, President Johnson ordered sailors from Meridian Naval Air Station to augment state and federal law officers who were conducting the search.

There have been reports that they were seen in other states.

None of these reports proved out, and so far neither has the search.

JONES: On August 4, 1964, at the Mt.

Olive Missionary Baptist Church in Meridian, Mississippi, Pete Seeger gave a concert.

You know, we were all into James Brown and all that and here, you know, we got a guy who's a folk legend that comes to Meridian and we were told that he's going to do this concert.

PETE SEEGER: It was a small church, so there were about 200 people there, and I had been singing to them, I guess, on a slight raised platform, probably near the pulpit.

And I had gotten them singing with me.

JONES: And, all of a sudden, in the middle of a song that he was singing, someone came over and whispered into his ear.

He stopped and he got up and made an announcement.

SEEGER: "The bodies of Schwerner, Goodman, and Chaney "have just been discovered.

They were buried deep in the earth."

There wasn't any shouting.

There's just silence.

I saw lips moving as though they were in prayer.

He asked us to join hands and sing, ♪ We shall overcome, my Lord ♪ ♪ We shall overcome someday ♪ ♪ We shall overcome someday... ♪ (crowd singing "We Shall Overcome") ♪ Oh, deep in my heart ♪ ♪ Know that I do believe ♪ ♪ Oh, we shall overcome someday.

♪ SCHWERNER: I got a call late in the evening.

At least this... this nightmare of unknowing, or at least not officially knowing, was over.

CROWD: ♪ God is on our side ♪ WATSON: The bodies of Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner were flown to New York.

They had a separate funeral there.

Fannie Lee Chaney flew to New York to be at that funeral.

The families by then were so together, even though they had never met before.

The mothers locked arms and walked out of the church together.

CROWD: ♪ Oh, we shall overcome someday.

♪ WATSON: In Mississippi, a memorial service was held for James Chaney.

♪ ♪ DENNIS: The decision had been made by family members and local leaders and others that they wanted to keep this very quiet and then low key, rather.

I did their eulogy.

(archival): I want to talk about is really what I really grieve about.

I don't grieve for Chaney because of the fact I feel that he lived a fuller life than many of us will ever live.

I feel that he's got his freedom and we're still fighting for it.

WATSON: Dave Dennis's speech was a turning point in the summer because everybody wanted him to say the usual things that you would say at a funeral.

And Dave Dennis just couldn't do it.

He challenged the people at the memorial and he challenged the whole movement.

You see, we all tired.

You see, I know what's gonna happen.

I feel it deep in my heart when they find the people who killed those guys in Neshoba County... All the different emotions of things we'd been going through leading up to this particular moment began to come out, boil up in me, you might call this.

And then looking out there and seeing Ben Chaney, James Chaney's little brother, I lost it.

I totally just lost it.

Don't bow down anymore!

Hold your heads up!

We want our freedom now!

(voice breaking): I don't want to have to go to another memorial.

I'm tired of funerals.

Tired of it!

We've got to stand up!

CROWD: ♪ Oh, oh, oh, deep in my heart ♪ WATSON: I think a lot of people in Mississippi, white people, thought, "If we could just repel them with the violence, they'll go away."

But the beauty of Freedom Summer was the tenacity shown by the local people and the volunteers by staying on and on despite the violence, despite the threats, despite the three bodies.

That created a momentum that, as it went on into August, you did begin to see more people showing up at mass meetings, more people showing up at church.

♪ ♪ WOMAN: ♪ Well, this little light of mine... ♪ CROWD: ♪ I'm gonna let it shine.

♪ WATSON: Churches that had originally had maybe ten or 12 people for an evening meeting, and there were evening meetings almost every night, now you got 20, 30, 40, 50 people showing up.

The churches are filled in the evening.

Just being there in Mississippi is making a difference.

CROWD: ♪ Let it shine, let it shine, let it shine... ♪ WOMAN: ♪ Tell Governor Wallace... ♪ CROWD: ♪ I'm gonna let it... ♪ HARRIS: The mass meeting was called by the community.

That was the purpose of the mass meeting, to bring people up to date, don't have any fear.

Try to stick to your grounds and you are eligible to become a registered voter.

Don't have any fear.

It made us stronger.

As the time grew, then the crowds started getting larger.

(crowd singing) HARRIS: My friends and I, my brothers, we would sit on the front pew at a meeting.

And our role as young people was to stand up in front of the congregation and begin singing freedom songs, all a cappella, clapping our hands.

And the congregation would be on its feet and they're swaying from side to side, and we're singing these songs like "Ain't Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me 'Round, Oh Freedom."

JONES: They would break out and sing, ♪ This little light of mine ♪ ♪ I'm gonna let it shine... ♪ CROWD: ♪ I'm gonna let it shine... ♪ (vocalization continues) WATKINS: On my project, the volunteers, all of them, had to go to the mass meetings.

CROWD: ♪ I'm gonna let it shine, let it shine, let it shine... ♪ SIMMONS: It played for them, I think, the same role that it played for Black people.

Because it was infectious.

It galvanized you.

It fortified you.

It enabled you to go on.

SINGER: ♪ Let me tell you, everywhere I go... ♪ MILLER: When you're in a situation with that much fear and every day not knowing what's going to happen, when you're in a mass meeting you feel... there's a feeling of safety, there's a feeling of strength.

Everyone was there to change things.

And so when you're in those mass meetings, you really believe you can.

CROWD: ♪ I'm gonna let it shine ♪ ♪ Let me tell you, my Lord gave to me ♪ ♪ Well, I'm gonna let it shine, let it shine ♪ GRAY: We have organized into the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

We're holding a Freedom Registration drive throughout the state, encouraging every Negro and white who wants a stake in his political future to prove it by getting his name on a Freedom Registration book.

CHRIS WILLIAMS: The word came down from the office in Jackson that, "All right, this has gotta be the priority."

Bob Moses said, "We gotta really concentrate on this, "we've got to sign people up for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party."

We were going to go to Atlantic City with a delegation of Black Mississippians to challenge the white delegation at the Democratic National Convention.

ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON: Our case was pure and unadulterated exclusion and discrimination.

We regarded the delegation sent from Mississippi, an all-white delegation, as illegitimate under the rules of the Democratic Party, and we argued that our integrated delegation from all of the counties in the state should be seated instead.

♪ ♪ PEGGY JEAN CONNOR: Those students helped us get people registered.

We registered thousands of them.

I guess people were just fed up.

People were hunting you to register to vote.

You didn't have to just go to their house.

They wanted to put their name on.

WILLIAMS: Any place people congregated, we're there with our forms.

It wasn't complicated like the official voter registration form, and it was confidential.

It wasn't going to pass through the hands of the white people down at the courthouse.

We have scheduled precinct meetings and district caucuses, and on August 6 here in Jackson, we will hold our state convention.

At that time, we will elect a slate of delegates to the national convention in Atlantic City.

♪ ♪ ED KING: The delegates came from all over the state.

Most of the delegates had never taken part in anything like this in their lifetime.

♪ ♪ PEGGY JEAN CONNOR: I was happy really, really, because I did not think I would be a delegate.

I didn't.

And I was one of the first ones that they selected.

♪ ♪ (cheering) SIMMONS: It was a wonderful experience to see these people who had been oppressed and killed for trying to register to vote taking over their own destiny.

For the first time, doing something that I think they'd never imagined being able to do.

(banging gavel) Will the delegates please be seated.

The state convention for the Freedom Democratic Party is now in session.

KING: Out of 68 people in the delegation, four were white.

The regular delegation was all white, had no Blacks.

So we are integrated at that point and they are not.

BRUCE WATSON: Joseph Rauh agrees to be the chief counsel for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

Rauh is a Washington insider from way back in the '40s and he had worked with all sorts of liberal causes and politicians.

He was a lawyer for United Auto Workers and very powerful, and that's a great person to have on your side.

REPORTER: Mr. Rauh, what is your dispute with the regular Mississippi Democratic delegation?

Very simple.

They are disloyal to the national party.

They exclude Negroes who would help the national party from their roles.

They have engaged in the terroristic activities in Mississippi... JOHN DITTMER: The people in Mississippi didn't know how national politics work.

They didn't know how conventions work.

Rauh did, and he was the one who said that, "I think we can do this."

♪ ♪ SHERWIN MARKMAN: I can't overstate how seriously Johnson took this whole thing.

He believed that Bobby Kennedy, who was then attorney general, was going to use any disruption at the convention as a vehicle to displace him as the nominee.

The second thing he was concerned about is he wanted to keep the regular Southern wing of the party in the party, that that the whole battle would cause a split within the party, which would drive out the regular Southern states.

And he believed that without the South's support, he would lose the election.

So I was designated to go to the convention as a delegate to make sure that did not happen.

CHARLES McLAURIN: We had Democratic congressmen from Illinois and from other states.

The Democratic Party was the party of Adam Clayton Powell, so we felt we had an inroad there.

If they let us state our case, we would be seated.

SINGES: ♪ Get on board!

♪ ♪ Children, children, get on board ♪ ♪ Children, children, let's fight for human rights ♪ ♪ I hear those mobs a-howling and coming 'round the square ♪ ♪ Trying to catch those freedom fighters ♪ ♪ But we're gonna meet you there ♪ ♪ Get on board, children, children ♪ ♪ Get on board, children, children ♪ ♪ Get on board, children, children ♪ ♪ Let's fight for human rights... ♪ McLAURIN: I think that trip must have taken...

I guess, 20 hours.

I'm not sure; it was a long trip.

But the mood on the bus was upbeat.

Here we are going to Atlantic City to unseat the people who had denied us the right to vote.

So it was really a jubilant time to me.

We stepped out into a new world.

(band playing marching tune) REPORTER: On Monday, the 1964 Democratic National Convention will open here in Atlantic City, a resort 100 miles south of New York.

The job will be to nominate President Lyndon B. Johnson as the man to take on Senator Barry Goldwater in the presidential election battle in November.

Known as Convention City and home of the Miss America contest, Atlantic City can now claim the honor of a national political convention.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: These people were beauticians and farmers and mechanics and they had kind of baggy, worn suits and funny looking dresses in some cases.

They weren't slick like the rest of the delegates were, so people weren't quite sure what to make of these people.

FANNIE LOU HAMER: We believe that we will be seated in this convention because it is right.

When you tell the truth, you don't have anything to hide.

KING: Outside the convention hall, we had a vigil, went on 24 hours every day that the convention was in session.

KARIN KUNSTLER: It was, you know, great for us who had spent time in Mississippi to see not only people from Mississippi there and not only volunteers there, but larger groups of people who came from all over to support the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

I know the boardwalk was covered with people.

I think it was hard to walk down the boardwalk because there was so many of us.

♪ Go tell it on the mountain, over the hills and everywhere ♪ ♪o tell it on the mountain to let my people go... ♪ RITA SCHWERNER: The whole notion of the demonstration out on the boardwalk and the MFDP challenge was all by way of trying to use the attention that would be focused on the convention to say to the country, "Look at Mississippi.

"Look at what is going on there.

You cannot allow this to continue."

♪ Go tell it on the mountain to let my people go.

♪ ♪ ♪ NORTON: We had to go to the delegations from the various states to make a case that had never been made before: that an official delegation that came from a state should not be recognized, and an entire challenge delegation should be recognized in its place.

MARKMAN: They were very confident coming to the convention.

They had every reason to be confident.

The Mississippi Freedom Party had morality on their side, which is a powerful force in politics.

So this was a revolution that they were starting within the Democratic Party.

REPORTER: Mr. Rauh, when will the fight come, and how?

Well, the fight comes this way.

On Saturday afternoon, there will be a hearing before the credentials committee, and we will present our case.

DITTMER: This was before the convention actually formally met.

These 108 people would listen to the Freedom Democrats, then if 11, only 11 members of that committee would file a minority report, that would mean that it would go to the convention floor.

In front of a national television audience, why, the Freedom Democrats would win because their case, of course, was so strong.

REPORTER: Are you hoping that President Johnson will come out on the side of your party?

RAUH: No, I think that'd be a mistake.

I think it would be a mistake for the president to take sides, even our side.

All we ask for is benevolent neutrality, by which I mean real, honest-to-goodness neutrality.

JOHNSON: I don't know how anybody can stop what they're doing on the Freedom Party.

I think it's very bad, and I wish that I could stop it.

I've tried, but I haven't been able to.

Last night I couldn't sleep.

About 2:30 I wake up.

TAYLOR BRANCH: Lyndon Johnson literally was so fearful that the convention was going to blow up that he essentially went to bed for two or three days and had what amounted to a nervous breakdown.

He told his closest advisors and his closest friends that he was going to quit, that he couldn't take the pressure.

JOHNSON: I do not believe I can physically and mentally carry the responsibilities of the world, and the Niggras, and the South.

I thought about it a good deal this morning.

(crowd chattering) DITTMER: The testimony before the credentials committee, the FDP had a lineup of very different people.

They had Rita Schwerner, the widow of Mickey, who had been killed in Neshoba County.

They had Martin Luther King.

Everybody knew King.

The seating of the delegation from the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party has political and moral significance far beyond the borders of Mississippi, of the halls of this convention.

DITTMER: But the highlight of the testimony was that of Fannie Lou Hamer, the sharecropper who had been evicted from her plantation and had come to symbolize the Mississippi movement.

HAMER: Mr. Chairman, and to the credentials committee.

It was the 31st of August in 1962 that 18 of us traveled 26 miles to the county courthouse in Indianola to try to register to become first-class citizens.

We was met in Indianola by policemen.... BOB MOSES: The president, Lyndon Johnson, he's not afraid of Martin Luther King's testimony.

He's afraid of Fannie Lou Hamer's testimony.

And so he decides that the country should not see her testify live.

BRANCH: Johnson is in the White House and he convened an impromptu press conference.

We will return to this scene in Atlantic City, but now we switch to the White House and NBC's Robert Goralski.

Now, ladies and gentleman, the president of the United States.

On this day nine months ago...

BRANCH: He did it knowing that they would break away, thinking he might announce who his choice of vice president was going to be.

Instead he gets up there and he announces-- get this-- he announces that it's nine months to the day since Governor Connally, who was there, was shot along with President Kennedy.

So he announced a nine-month anniversary.

Everybody's scratching their heads.

Thank you very much.

BRANCH: And then he leaves.

By that time, Fannie Lou Hamer's testimony was over.

(applause) However, it backfired on Johnson because it became a story that she had been taken off television.

And in the news that night and for days afterwards, they replayed her testimony.

HAMER: I was carried to the county jail and put in the booking room.

They left some of the people in the booking room and began to place us in cells.

MOSES: She had Mississippi in her bones.

Martin Luther King or the SNCC field secretaries, they couldn't do what Fannie Lou Hamer did.

They couldn't be a sharecropper and express what it meant, right?

And that's what Fannie Lou Hamer did.

HAMER: And it wasn't too long before three white men came to my cell.

One of these men was a state highway patrolman.

He said, "We going to make you wish you was dead."

I was carried out... LARRY RUBIN: I was in Mississippi watching it on television with local people.

This was a transformative moment for the folks in that room.

This was the first time that they ever had seen one of their own, a Black Mississippian who they all knew, first of all, on television, secondly, standing up for their rights.

I began to scream, and one white man got up and began to beat me in my head and tell me to hush.

CHARLIE COBB: You listen to Mrs. Hamer and you're absolutely convinced that there's absolutely no justification for seating this all-white delegation.

HAMER: And if the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America.

Is this America?

The land of the free and the home of the brave?

Where we have to sleep with our telephones off of the hook because our lives be threatened daily.

Because we want to live as decent human beings in America.

Thank you.

(applause) REPORTER: That testimony, offered in public session last Saturday, we are told had the greatest impact on the women members of the credentials committee and it is from among them that a sufficient number has been found to make a minority report possible.

EDITH GREEN: The Freedom Democratic Party has done everything in its power, as I listen to the testimony, to abide by the laws and rules of Mississippi.

I think they ought to be seated in this convention.

I think they represent about 50% of the population of Mississippi, all the Negroes in Mississippi who are excluded from voting and participation in the regular Democratic Party.

And I think certainly, they're entitled to representation.

♪ ♪ COBB: There was a lot of sympathy for seating this Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

But once you see that Lyndon Johnson has shut down Mrs. Hamer during her live testimony, you can't help but wonder, "What else is he going to do?

"And how are these delegates going to respond when there's real pressure placed on them?"

♪ ♪ JOHNSON: Hell, the Northerners are more upset about this.

They call me and say that the Negros have taken over the country.

They're running the White House, they're running the Democratic Party.

WALTER REUTHER: Yeah.

JOHNSON: And they don't understand that.

They're there before that television.

They don't understand that nearly every white man in this country would be frightened if he thought the Negroes were to take him over.

DITTMER: People who were on the credentials committee who were listed as being supportive of the challenge found that...

In one case, a woman said, "Well, your husband isn't going to get that judgeship."